The Golds of Roccagloriosa

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam.

The Ori are undoubtedly among the most striking artefacts of the Lucania site of Roccagloriosa and constitute the original and inspiring heart of this journey among the jewels of the Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni National Park area, whose values recognised by UNESCO they fully express. The jewellery complex, comprising a breastplate, two rings, an armilla and several fibulae, comes from an ancient burial outfit of a young woman who lived between the 3rd and 4th centuries BC. C. was brought to light in 1976/1978 during excavations conducted by Maurizio Gualtieri and is now on display in the antiquarium dedicated to the archaeologist Antonella Fiammenghi, a figure from the Salerno Superintendency remembered for her commitment and passion in safeguarding and enhancing the cultural resources of Cilento.

The precious Ori of Roccagloriosa are unique jewellery within the local context, and it is precisely this richness and uniqueness that lead one to believe, on the one hand, that this young woman belonged to the high ranks of the ancient community of Roccagloriosa and, on the other hand, that their production cannot be attributed to a local manufacture. Maurizio Gualtieri, who after Mario Napoli conducted the archaeological research at the Roccagloriosa site from 1976 onwards, has hypothesised a Taranto provenance, one of the great goldsmiths' centres of ancient Italy on which we will focus.

When speaking of jewellery in ancient southern Italy, one cannot fail to mention Sardinia with the Phoenician-Punic city of Tharros that, in the Mediterranean dominated by the ships of Carthage, spread its jewellery far and wide. Culturally varied jewellery that expressed not only its own matrices but also Egyptian and Assyrian elements that the Punic world had absorbed, proposing themes and forms originating in the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia. Or we cannot overlook the centres of Etruria, which had learnt and innovated tastes and techniques from the East. The Etruscans, even where they did not arrive militarily, left with their goldsmith's art a tangible sign of their dominion and influence. Having waned, with their political decline, the influence that the Etruscans had exerted over such a vast area of ancient Italy, it is above all in the centres of Sicily and Magna Graecia that we see, from the 4th century onwards, the goldsmith's art assert itself and flourish, especially in Tarentum, which, in the general decay of the Siceliote and Italiote colonies, was the last great political and cultural state of the Greeks in the West.

the only Spartan colony outside of Greece, played a leading role in the scenario of the Italian peninsula, becoming a cultural, commercial and military reference point for the entire south, pushing its influence as far as Rome to some centres in Etruria. In this context, workshops and goldsmiths developed that reached a very high level and a wide mixture of technical and stylistic influences, also due to the presence of not only indigenous but also Greek and Etruscan workers. Gold jewellery in Taranto is distinguished by the variety, quality and refinement of its artefacts, which range from women's jewellery, such as necklaces, earrings, bracelets, rings, diadems, hair nets, to men's jewellery, such as fibulae, brooches, belts, helmets, to ritual jewellery, such as sceptres, crowns, vases, statuettes and appliqués. The materials used are mainly gold and silver, but also bronze, iron, ivory, rock crystal, semiprecious stones and pearls. The techniques used are those of casting, rolling, filigree, granulation, embossing, engraving, inlay, setting, niello, gilding and patination. The decorative motifs are inspired by nature, mythology, religion, local culture, but also by oriental and Etruscan influences. Tarentine goldsmithing is one of the most refined and original expressions of the art of Magna Graecia and still today constitutes the keystone for the study of techniques and styles of the classical and Hellenistic age and, in general, a point of reference in the study of the history of jewellery. We do not know the names of ancient goldsmiths from Taranto, but several pieces of jewellery - kept mainly in the National Archaeological Museum in Taranto - seem to have been mass-produced, albeit in different sizes; other pieces of jewellery seem to have come from the same workshops.

Un altro studioso, Pier Giovanni Guzzo, che è l’unico ad essersi soffermato in maniera specifica in analisi tipologiche degli ornamenti di Roccagloriosa, in due pubblicazioni - Oreficeria della Magna Grecia e Oreficerie dell’Italia antica - ha evidenziato come il corredo della Tomba 9 rimandi ad ambiti culturali molto diversi tra di loro e ha ipotizzato come questi monili possano essere stati acquisiti attraverso i contatti commerciali legati alla attività di trasformazione di prodotti agricoli oppure all’attività di mercenariato diffusa tra le popolazioni italiche e, quindi, anche essere oggetto di bottino.

Another scholar, Pier Giovanni Guzzo, who is the only one to have focused specifically on typological analyses of the ornaments from Roccagloriosa,in two publications - Goldsmiths of Magna Graecia and Goldsmiths of Ancient Italy - has pointed out how the Tomb 9 ornaments refer to very different cultural spheres and has hypothesised how these jewellery may have been acquired through trade contacts linked to the processing of agricultural products or to the mercenary activity widespread among the Italic populations and, therefore, also be the object of booty.

The jewellery leads us to imagine, even with great suggestion, the relationships woven by the ancient Lucanian community of Roccagloriosa and to highlight how emblematic they are of the 1998 WHL-UNESCO recognition. The fact that the armilla has compositional peculiarities that can be found in some Black Sea bracelets is significant and suggestive for the scholar as much as for the merely curious, leaving one to imagine and fantasise about the 'mental agora' that was the ancient Mediterranean, as defined by Michele Gras. An enclosed space at the centre of the world, a place of encounters and clashes, relationships, competition and emulation. The jewels of Roccagloriosa, observed with a more conscious gaze, fully and truly express the distinctive features that led the Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni National Park to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List:

“Cilento is the point of intersection between the sea and the mountains, the Atlantic and the Orient, the Nordic and African cultures, it has produced peoples and civilizations, and it retains clear traces of this in its distinctive characteristics. Located in the heart of the Mediterranean, it is the park par excellence because the most typical aspect of that sea is the interpenetration and diversity of environments and the coming together of peoples.”

Among the favourite styles of bracelets in the ancient world was the armilla, an arm and forearm ornament consisting of an open ribbon-like spiral. This was a model already known and in use by primitive civilisations and very popular in ancient dynastic Egypt and later among the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans. The bracelet of Roccagloriosa is composed of an open ribbon band with knurled edges, i.e. grooves impressed in the metal that create a sort of beading. The ends of the bracelet culminate in snake heads, finely engraved and chiselled, the rendering of the details bringing out the scales of the snake's skin. Also noticeable on the heads of the animals is a peculiar zig-zag engraving obtained by means of a chisel with a washer that left a real engraved ribbon, a sort of modern granelliere.

These heads are welded to the base of the twisted band, and at the welding point where the band turns into a snake, we find an embossed sheet with two opposing human heads, female and male, and both represented in youth and then old age, alluding to birth and death and thus to the cyclical nature of life. This call to cyclicity is, however, already typical of the symbolism of the serpent, which, in addition to being chosen as a religious symbol, was more generally and more ancestrally considered as a polyvalent symbol of good and evil, of poison and antidote, but above all for its esoteric meanings of regeneration and eternal life. The serpent is a polyvalent and polysemic symbol, expressing the different facets of the human being and his relationship with the sacred, the natural and the supernatural. An animal that has always aroused fascination and fear in the human imagination, entering into the mythology and symbolism of many ancient cultures, often representing the principles of existence, such as life, death, regeneration, wisdom, power and temptation.

There are several gold rings from Roccagloriosa, one found in Tomb 14 with an engraving of a female figure, seated and with her hair tied up while holding a bird, and two others from the rich grave goods in Tomb 9 and exhibited in the Antonella Fiamenghi Antiquarium. Of the rings on display, there is one, which is very common, with a beetle engraved in a carnelian using the 'globule' technique, i.e. in which the image is not depicted in detail but results from the engraving of oval or rounded grooves. This ring is composed of a gold hoop that echoes another ancient Greco-Doric ring 'design' with an engraved carnelian in the form of a globule signet ring (σφραγίς) that was widespread among the Egyptians, which was introduced by the Sumerians with a cylindrical vague with cuneiform engravings that served to seal their identity. The ovalising carnelian is pierced on both sides; this through-hole allows the stone to be pinned to the shank with the thread running through it. The stone is protected from rubbing against the shank by two hemispherical gold cups that block the stone, so the wire passing through them then twists on the shank.

The gold thread closes and stops an oval bezel with an engraving of an animal-type figurative design, very common in the Italian glyptic tradition, different from the Hellenistic one, which in fact preferred mythological representations and narratives. Already in archaic times, this type of digital ring was the exclusive prerogative of female ornamentation, signifying and marking the power exercised by women within the domestic and conjugal spheres. Sealing rings such as these, with stones or hard pastes, were to be rivet-mounted or with twisted wires, so that they could rotate and be set in the ring itself without beating, soldering or adhesives.

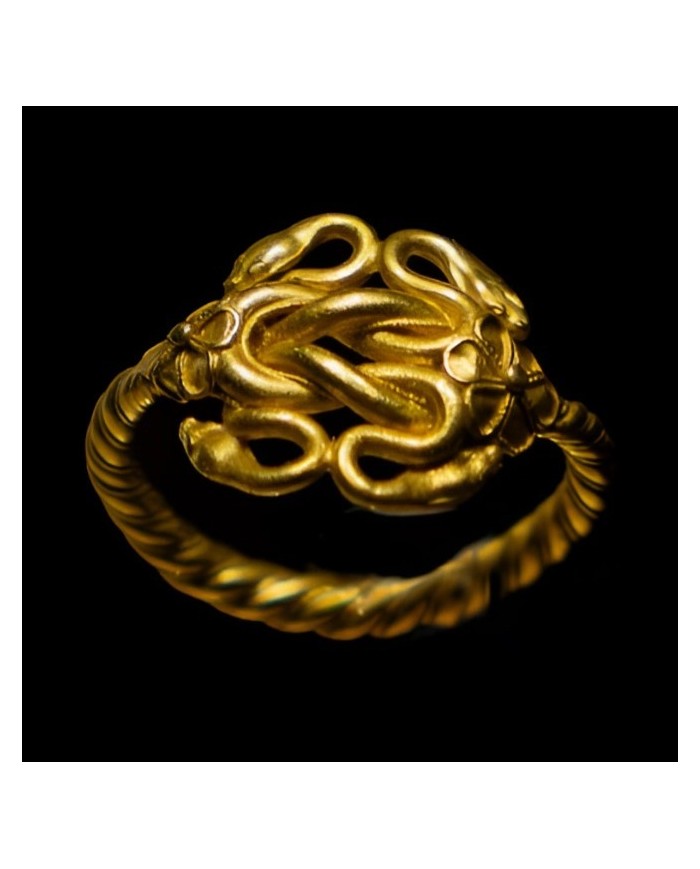

The most fascinating of Roccagloriosa's rings is the one with the Node of Heracles, which has also become an icon of the Cilento village of Roccagloriosa. This all-gold ring made of two smooth intertwined threads can tell us a lot about the wearer, not only with reference to wealth but also to the emotional sphere: the nodus heracleus is in fact also known as the 'knot of love' and is a symbol of fertility, suggesting an emotional bond. The name originates from one of the twelve labours of Hercules, the one in which the hero defeats the terrible Nemean lion that terrorised the region, whose skin was used as a cloak by fastening it around his neck with a double knot. But the nodus heracleus in ancient Rome was also used at weddings to tie the bride's garments, to be untied at night by the groom.This digital gold ring is composed of two twisted strands of wire to the contours of which is soldered a very fine micro-beaded knurled wire in the form of granulation. The latter, at the top, intertwines to form the knot and then ends in four snake heads. The heads and all details such as the eyes are finely chiselled. At the knot attachments we find two rosette-shaped flowers with the contours defined by a knurled micro-thread in the form of granulation with a soldered micro-thread in the centre that acts as a pistil.

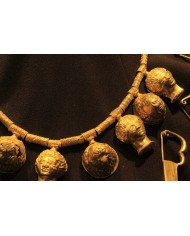

The most important piece of the Ori of Roccagloriosa is certainly the necklace, an unmistakable sign of power and social prestige. Necklaces and breastplates enjoyed growing popularity in the Late Minoan and Mycenaean periods and, between the 5th and 5th centuries, became among the most widespread ornaments. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods they became exquisitely feminine accessories, and the very Latin term for necklaces, munus or gift (hence monile), underlines how in ancient times they were a typical gift from the husband to his wife.Munus can also be translated as funeral. In fact, necklaces and breastplates such as these were created either as wedding gifts or to be used to set out funeral garments and trousseaus or even religious rites.

.png)

Human head and lion protome pendants, each with small cylinders for suspension decorated with wave-welded threads. These elements were to be inserted into a lace made of linen, leather or woven fabric and fibre. Overall, the necklace consists of nine pendants separated from each other by finely filigreed tubular elements. The recurring subjects in this type of necklace were naturalistic, floral and animal motifs, human and zoomorphic heads, lions, satyrs and other representative themes that were not limited to mere decoration but also had a real magical and apotropaic function. The gold foil of the suspended elements was completely embossed on the recto and chiselled on the verso. This is the ancient toreutic technique of Repoussè, from the French repousse, to push, repel, and therefore to emboss, which was then combined with other techniques such as granulation for the most exquisite artefacts, or as in this case with filigree and knurling or beading to simulate a sort of granulation. Every female and lion's head has a knurling edge. This much more painstaking technique would later be replaced and exemplified by the stamping technique with which the figure was impressed in relief and then finished with a burin and chisel. These female heads are found both in the goldsmith production of Taranto and Metapontum and in the finds from the treasure of the Priestess of the Ori of Buccino.

Fibula is the Latin term by which fibulae or brooches were called, i.e. those instruments used by both men and women to close and fasten garments and cloaks. They were much more than simple ornaments, protecting and sealing inner virtues and representing love, friendship and faith. In this trousseau we find no less than fifteen of them. Eight of these are made of gold with a double hump and a button-ended bracket; the very long and pronounced bracket is made of folded sheet metal that forms a square wall to hold the pin. It is difficult to establish the provenance of these clasps, also because although there are numerous finds of this double hump model in silver in southern Italy, including Paestum and Buccino, there is only one other pair of specimens in gold with a double hump - albeit of a slightly different shape - found in the rich funeral trousseau from Roccanova, in the province of Potenza. The other seven buckles from Roccagloriosa are in silver, smaller in size, have a single simple arch, a laminated stirrup with an engraved swastika and, Guzzo notes, originally had a small cylinder made of coral or glass paste inserted at the end. The swastika, a word derived from the Sanskrit स्वास्तिक, which can be translated as luck/well-being/prosperity, is a symbol that appeared as early as protohistoric times used as an amulet or sign of good luck. Widespread in the Far East and especially in India and China, it also found wide diffusion in other regions of Eurasia and we find it as a constant in many artefacts from the Mediterranean area and the ancient world. The shape of the swastika refers to the universe, the stars and their motion and is also directly associated with the Sun.

Found at the left hand of the deceased, it was one of the funerary objects of practical and not just decorative use. The production of bronze mirrors is attested in Greece as early as the second half of the 8th century B.C., reaching maximum popularity in the 6th century. The Speculum is generally composed of a circular reflecting disc and a handle with a connecting element usually with a relief engraving of a plant or zoomorphic subject or elements subsequently welded and made of lost wax or moulding. The disc is vaguely convex on one side and concave on the other. The oldest example of a mirror is the handle mirror. Such toilet accessories are widely attested in domestic and funerary trousseaus. In the Hellenistic period especially, they feature exquisite designs, engravings and refined materials.

- Gioielli, breve storia dall'antichità a oggi, Clare Phillips, Rizzoli (2003);

- Gli ori di Taranto, Autori Vari, Italsider (1975);

- Granulazione etrusca. Un’antica tecnica orafa, Gerhard Nestler, Edilberto Formigli, Nuova Immagine Editrice (1994);

- I metalli del mondo antico. Introduzione all'archeometallurgia, Claudio Giardino, Edizioni Laterza (2010);

- I greci in Occidente, a cura di Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli, Bompiani (1997)

- Il Mediterraneo nell’Età arcaica, Michel Gras, Fondazione Paestum (1997);

- L'oreficeria nell'arte classica, Filippo Coarelli, Fabbri Editori

- L’oro in Italia, Mario Petrassi, Editalia (1985)

- La metallografia nei beni culturali, a cura di Mauro Cavallini e Roberto Montanari, AIM Associazione italiana Metallurgia (2003);

- L’oro degli Etruschi, a cura di Mauro Cristofani e Marina Martelli, Istituto Geografico De Agostini (2000);

- Magna Grecia, Vol. IV, Arte e artigianato, a cura di Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli, Electa (1990)

- Megale Hellas. Storia e civiltà della Magna Grecia. Autori Vari, Libri Scheiwiller (1983);

- Miniere e metallurgia nel mondo greco e romano, John F. Healy, “L’Erma” di Bretschneider (1993);

- Oreficeria della Magna Grecia, Pier Giovanni guzzo, Scorpione editore (1993);

- Oreficerie dell’Italia antica, Pier Giovanni Guzzo, Ferrari Editore (2014);

- Ori del Museo nazionale Archeologico di Taranto, Amelia De Amicis, Laura Masiello, Scorpione editore (2017);

- Ori e argenti dell’Italia antica. Torino, Giugno-Agosto 1961, Autori Vari, Edito dal Comitato promotore della mostra (1961);

- Oro, gemme e gioielli. I dizionari dell'arte, Silvia Malaguzzi, Electa (2007);

- Roccagloriosa I, Maurizio Gualtieri ed Helena Fracchia, Centre Jean Berard (1990);

- Roccagloriosa II, Maurizio Gualtieri ed Helena Fracchia, Centre Jean Berard (2001);

- Roccagloriosa. I Lucani sul golfo di Policastro, Maurizio Gualtieri, Lombardi editori (2012);

- Storia dei gioielli, Anderson Black, a cura di Franco Sborgi, Istituto Geografico De Agostini (1973);

- Tecniche dell’oreficeria etrusca e romana. Originali e falsificazioni, Edilberto Formigli, Sansoni (1985);

- Tra caduceo e preda di guerra. A proposito del sauroter iscritto da Roccagloriosa, Raimon Graells i Fabregat e Luigi Vecchio, in La Parola del Passato (2018/2), Leo, S. Olschki Editore (2018);

15 June to 15 September Monday-Sunday from 17:30 to 20:30. The rest of the year open by appointment; Tel. +39.0974.981113 (Municipality) +39.349.2201533 - +39.329.4453319 (Proloco)